Diana Quinn Inlak’ech: the struggle for liberation includes reclaiming space for grief and healing

This post is the first in a series on Grief Care, featuring BIPOC healers across multiple traditions and modalities talking about their work, how they’re meeting these deeply challenging times, the grief they’re carrying and how they’re tending to it, and holding space for their communities at the intersections of healing and justice.

Today, I talk with Diana Quinn Inlak’ech, a licensed naturopathic doctor specializing in somatic bodywork, integrative mental health, and decolonized healing modalities within a politicized framework.

The last few months have been a time of such profound grief and trauma for so many across the globe: what are the griefs you’re sitting with right now?

There are so many griefs I’m sitting with in these times. Grief for the many people we’ve lost to COVID-19 and for the ways the pandemic has highlighted the structural devaluing of the lives of Black, brown, disabled, sick and elderly people. Grief for those who have been violently robbed of their lives, for victims of racial injustice and cruelty and for their families and communities. Ancestral grief from colonization, for the loss of ancestral traditions and healing ways through forced assimilation. And planetary grief; Robin Wall Kimmerer talks about “species loneliness,” the grief of feeling estranged from our kin in the natural world, the grief from loss of species, from the threat of loss of ecosystems, of indigenous peoples and their languages.

Given how overwhelming it can be to even acknowledge that what we’re feeling is grief, what are some of the grief responses you’ve come to recognize in your own physical, spiritual and emotional bodies?

Grief and especially untended grief can show up in the body as various symptoms including pain, digestive complaints, or flare-ups of chronic health problems. For me, intense grief and distress can cause a flare-up of chronic pain or a migraine. I’m prone to neurological symptoms, like having trouble sleeping or increased intolerance to stimulation. Emotionally and spiritually, grief can feel like a heaviness. There is a certain sensation of weightedness and fatigue that I interpret as a manifestation of historical trauma and unresolved grief, or ancestral grief. When I experience this in my body, I find it helpful to remember that not everything that I’m feeling is necessarily “mine.”

When you recognize that grief response in you, what’s your natural inclination?

When I am feeling deep in a grief response, my impulse is to get near water, preferably a large body of water, or moving water like a river or stream. The best form of medicine for me personally is my beloved Lake Michigan, Ininwewi-gichigami here in Anishinaabe Aki. I also use baths therapeutically to soothe grief and emotional weight, with lots of Espom salts and plants or flowers that alleviate sadness like basil, rose and lavender.

What does it look like for you to tend your grief?

Tending to my grief looks like surrounding myself with beauty as much as possible: fresh flowers, candles, burning sacred plants. Creating an altar that is specific for this time with elements that feel spiritually supportive to help with moving through it. Preparing delicious food and herbal teas to nourish me throughout the day. Taking lots of baths. Listening to soothing music. Allowing myself to feel and cry and let the process unfold as it needs to, trusting the process. Spending time in nature as much as possible, and lying on the earth. Leaning on my spiritual practice of breathwork, prayer and meditation.

The work you do with your clients includes multiple modalities, from craniosacral therapy and somatic bodywork to Reiki, intuitive healing and plant medicine: is there a core philosophy or belief you bring to your work?

Very much so; the core philosophy is the path of the heart, which is a dedication to getting as clear as possible in order to get out of the way, to be present not as a “healer” but as a conduit. This foundation weaves through the various modalities within which I work, which all honor the healing potential and wisdom within the individual as both an innate intelligence of the body as an elemental made from earth, water, fire and air and imbued with spirit. Although I have formal medical training, I very much prefer connecting with people in a heart-to-heart way rather than through the intellect when doing healing work.

Can you share how one of these practices, or any combination of them, would support someone in accessing and moving through grief?

I consider touch to be so important, and working with the fascia and energy system through hands-on modalities like craniosacral therapy can be a profound tool for moving through grief. In these times of COVID, access to hands-on healing can be limited or unavailable. When I work with people remotely via video or phone, we use somatic practices that engage the body as well as energy work and heart-to-heart counsel. These are spaces that I hold for clients to help them connect with the support that is available to them, such as herbal medicine for the nervous system, certain foods that support movement of energy, or somatic practices that are supportive for moving through grief. In my experience, specific modalities are matched with the individual person, based on the resonance of energetics with what they are experiencing and the factors that influence the situation.

How is your work informed by ancestral and indigenous wisdom?

My work is deeply informed by ancestral wisdom, and through connecting with my ancestral lineages, the support from these relationships continue to grow. My ancestral lineages are indigenous to México and also from Europe, where you have to go much farther back in history to connect with indigenous wisdom. When I work with clients to establish a greater connection with their ancestors, the overwhelming response that they receive from their people is, “what took you so long?” I’ve come to believe that a big part of the sacred work that many of us came to do in these times is to restore our ancestral practices of grieving, tending to death and dying, and simply being in relationship with our ancestors.

What are some of the more common challenges or obstacles to grieving you see in your work?

Common obstacles are not allowing oneself to take the time, or not giving oneself permission to grieve. Living under capitalism, people are valued structurally based on our productivity, and we are granted less and less time for humanity. As Frederick Douglass said, “power concedes nothing without a demand”; it is part of the struggle for liberation to reclaim space for our humanity, including space for rest, space for collective care and mutual aid, space for grieving and healing from trauma, and space for joy and pleasure.

What wisdom or solace would you offer from the voice of grief?

You are a sacred being, and grief work is sacred work. Tending to your grief is tending to a piece of the grief of the soul of the world. Like all things it has its season, and like all things it will change. Although life is always changing, this is not the same as completion. In this way grief can be a wise teacher in helping us to become comfortable with trusting the mystery of life, death, and change.

One of the vital healing services you’ve been offering at this time is supporting the movement community. Can you speak to some of the ways that grief and trauma manifest in social movements, especially all these movement spaces we’ve been seeing across the country since the murder of George Floyd?

What we see in movement communities is very similar to the trauma affecting military veterans. The conditions that organizers and activists experience: the ongoing and urgent nature of movement work, the losses sustained with little time for processing, the pressure to constantly keep going because so much is at stake. Black and brown people have been in social justice movements for decades, strategizing, resisting, coalition building, taking action, getting ready — during these times everything is heightened by the pandemic and the sudden awakening of the larger culture to racial injustice. And truly, both because of the devastating impact of the pandemic on BIPOC communities and the looming climate crisis, there is urgency like we have never seen. Stress, grief, anxiety and depression are higher than ever in our communities. And with this, the awareness that we need to build healing into our movements is increasing. As an example to highlight this trend, there was a gorgeous photography series published in Rolling Stone magazine of healing practitioners in Minneapolis during the peak of the uprising there, where the Minnesota Healing Justice Collective and the Spiral Collective are based.

I would imagine many on the front and back lines of this work push their spiritual and emotional self-care to the side in order to show up as organizers and demonstrators: how are you helping them to combat the burnout, compassion fatigue and other stresses they experience?

You’re so right in your assessment about the ways in which care has been historically left out of movement, leading to burnout and fatigue. The Healing Justice movement was born out of the fact that movements for liberation occur within traumatic and traumatizing systems of oppression, and often reproduce structures that are ableist, individualistic, and haven’t made space for care and for us to show up in our full humanity. The term Healing Justice was coined by Cara Page and the Kindred Southern Healing Justice Collective back in 2008, out of an awareness of the historical and generational trauma that we are bringing to movements, and the concept that our collective healing is part of liberation work. Audre Lorde wrote, “caring for myself is not indulgent, it is self-preservation and that is an act of political warfare.” There are roots of this in the Civil Rights movement, with the Black Panthers providing acupuncture in their healthcare initiative and organizing school breakfast programs for children. The lineage of Healing Justice has been formalized since 2010 when the organizing principles were developed at the U.S. Social Forum and the Allied Media Conference. These principles are at the foundation of the work that I do in community with Healing by Choice!, a coalition of women of color and gender-non-conforming people of color based in Detroit. Currently we’re providing virtual healing spaces centered around care for stress, grief, anxiety and depression working with herbal medicine, somatic movement, mindfulness, and other modalities.

What would you consider an essential healing practice for anyone engaged with the national protest movement or otherwise fighting oppressive forces in this moment?

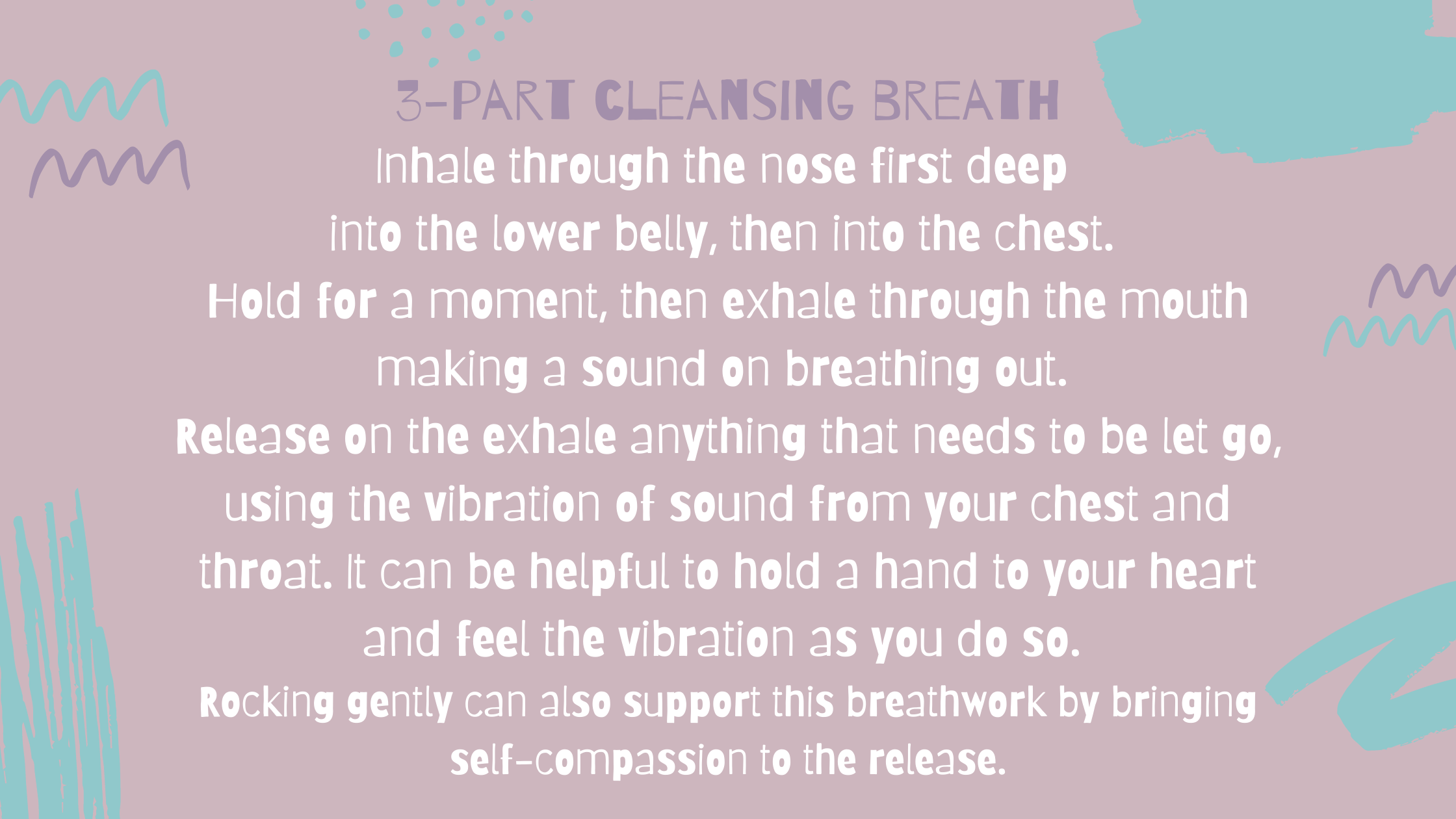

One of the most effective ways for building resilience, moving through emotions and clearing stress from our bodies is through breathwork. Working with the breath changes our physiology by regulating the autonomic nervous system, helping us to shift out of a depressive or anxious state. The breath is also a site of resilience and resistance: in claiming our breath we breathe for those who cannot, because of the virus or because it has been taken through violent force.

BIO

Dr. Diana Quinn Inlak'ech (she/her/hers) is a licensed Naturopathic Doctor fusing traditional and decolonized healing modalities alongside mind/body medicine at the intersections of social justice and spirituality. Through her trauma-informed practice, she specializes in somatic bodywork, integrative mental health, plant spirit medicine and botanical medicine, food as medicine, healing through ceremony and ritual, nature-based therapy and more.

She provides safer space to those who have been marginalized in medical industrial complex spaces including the 2SLGBTQIA+ community, Black, Indigenous and people of color, trauma survivors, differently abled folks and people of size (as a HAES advocate). She is a core collaborator with Healing by Choice!, a community of women of color and gender-nonconforming healing practitioners with a focus on self-care and the reduction of racial harm in mind, body, spirit and institution. She also provides 1-1 care and training for practitioners with TRACC (trauma and crisis care) for Movements.

Dive deeper into her work here.